Above: The Museum building, 1930. © Deutsches Hygiene-Museum.

As a student living in London in the early 2000s, I hosted a twentysomething visitor from Dresden, a city which had been in East Germany until 1990. He was a sophisticated if somewhat tetchy guy, dismissing my architectural studies as being concerned only with aesthetics. We didn’t talk much about Dresden, but I found him impressive.

In 2023 I got the chance to visit Dresden myself for the first time. I was keen to get an insight into the culture of the east German city. A major attraction for me was the baroque Frauenkirche, destroyed in the cataclysmic Allied firebombing of Dresden in February 1945, left in ruins throughout the DDR years, and rebuilt stone by stone between 1994 and 2000. My mother and I climbed the spiral ramp, inside the dome, to the lantern.

Dresden’s baroque architecture is marvellous, but it reflects the age of absolutism, and as such, resembles the monumental baroque architecture of other European cities. We came across another attraction in the city which is more particular and historically revealing. This was the large white museum, located in the Großer Garten park just to the east of the city centre.

Constructed between 1927 and 1930, this building has always housed the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum. The architect, William Kreis, combined rationalist and functionalist influences with a strong dose of conservative monumentality. He would later join the Nazi party and make a career building for that regime. Given this historical context, on encountering the museum one immediately wonders—“Hygiene? As in racial hygiene?” In fact the Hygiene-Museum had existed in one form or another since 1911 (long before Nazism) and continued to exist after 1945, through the socialist years and right up to the present day.

The notion of hygiene that the museum expounds purports to be a politically neutral one, originating in the all-encompassing normative hygiene movement of the late 19th century, which sought to remake the whole of life and society along healthier lines. As Bruno Latour puts it, “the boundaries of hygiene are vague”. No topic was off limits to the moralizing reformers:

[The movement] has no central argument. It is made up of an accumulation of advice, precautions, recipes, opinions, statistics, remedies, regulations, anecdotes, case studies… Illness, as defined by the hygienists, can be caused by almost anything… Nothing must be ignored, nothing dismissed.

Thus the hygiene movement was concerned with every scale of life, from microbiology to urban planning.

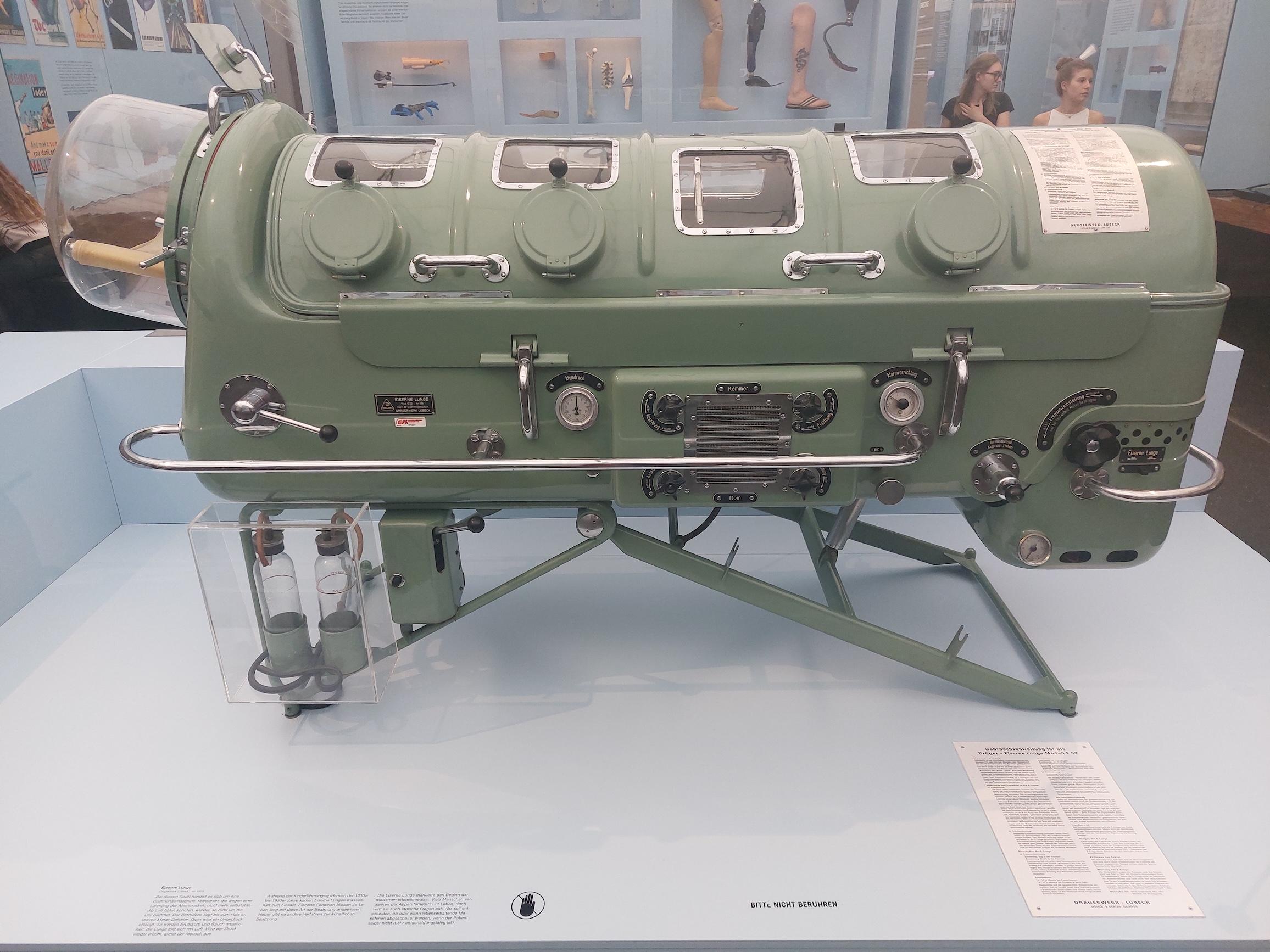

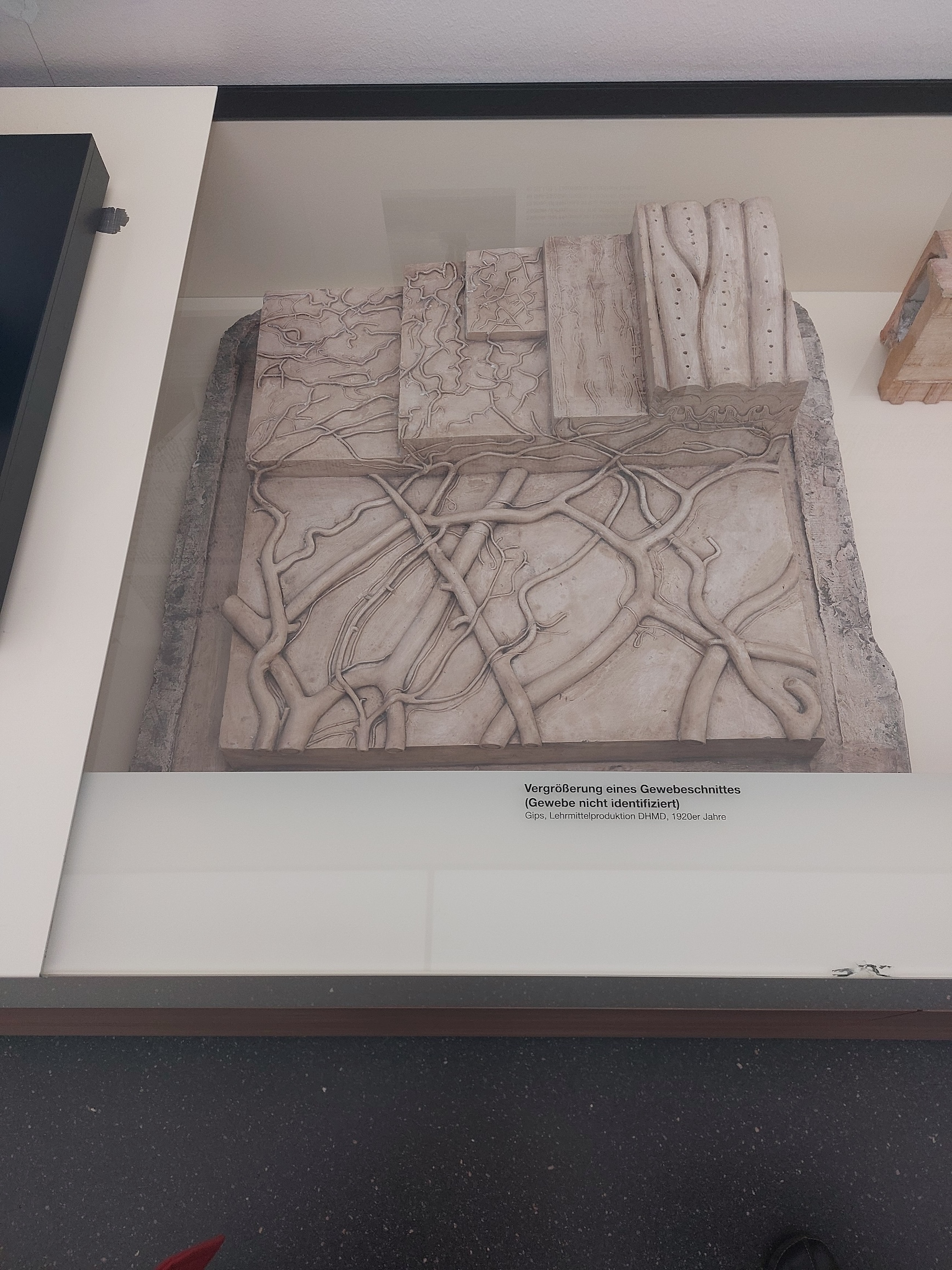

Dresden’s Hygiene Museum was founded (by the Dresden industrialist, and Odol mouthwash millionaire, Karl August Lingner) as a centre for the education of the public about health and healthcare in a very broad sense. Just as Odol mouthwash was a shrewdly branded product, the museum’s exhibits were sophisticated and used up-to-the-minute technologies. One of the most famous exhibits was a life-size Transparent Man, made with the new plastic Cellon (cellulose acetate) by the museum's own craftsmen.

Under Nazism, the Hygiene Museum unreservedly participated in promulgating racist ideology. Its expertise in communication was put in the service of Nazi propaganda. Somehow, when the war ended and denazification began, the new authorities deemed the museum to have a future as an educational asset, and it too was denazified.

There’s not much of this history to be seen, directly, in the immaculate interior of the museum’s galleries. In the years following German reunification, the museum received substantial institutional funding, facilitating the replacement of the aging displays of the DDR period. There is a permanent exhibition (The Human Adventure) on the top floor, and topical temporary exhibitions, in the same vein as those of the Wellcome Collection or Science Gallery Network, take place on the floor below. Today the museum’s agenda is “critical examination of the museum’s history, an interdisciplinary perspective on the human body, thematic diversity, and versatile, creative presentation.” Both the topical temporary exhibitions and the permanent exhibition reflect that agenda.

The permanent exhibition, currently to be seen on the top floor, dates from 2004/2006 and was curated by a team led by Bodo-Michael Baumunk. It is fabulous. The architecture of the displays was contributed by the Berlin architects Gerhards & Glücker, and is wonderfully solid, geometric and precise: terraced platforms and aedicular vitrines with a pattern of lights that evokes Alvar Aalto’s Viipuri Library. Nature’s correspondent said the following: “The display’s strong, simple and light design – the ultimate in German chic – creates an effect that is modern and learned, calm and uncluttered, despite the wealth of objects.” One might identify, in the design, the masculine pride in workmanship that seems to typify German style.

The exhibition occupies seven spacious rectangular rooms, each having its own theme: The Transparent Man, Living and Dying, Eating and Drinking, Sexualities, Remembering/Thinking/Learning, Motion, and Beauty, Skin and Hair. The first room is the one which reckons explicitly with the Museum’s history, while the remainder are more conventionally or, as it were, universally, didactic. Since the opening of the permanent exhibition nearly 20 years ago, a few of the rooms have been refreshed by new curators, which seemed in most cases to have diluted the excellence of the original design, in favour of participatory elements. One benefit of these changes, for me, is the introduction of English-language labels.

At the time of the opening of The Human Adventure, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung’s correspondent wrote:

“There are not many exhibitions which are so comfortably furnished … The light is pleasant, the colours subtle, there are places to sit everywhere and the exhibition is so cleverly designed that you don’t notice how often you find yourself standing in front of a display case looking at objects in the old-fashioned way.”

This question, of how conservative or progressive the exhibition is, seems central. The troubled history of the Museum’s support for the Nazi regime has informed a very long-established and fully developed curatorial approach of sensitivity and acknowledgement of racial and colonial injustice. As a result, in that specific respect, The Human Adventure, while largely a pre-digital exhibit, seems ahead of its time in comparison with museums in the UK. At the same time, the permanent exhibition is now quite old (nearly 20 years!) and so it represents a dated view of these issues.

A concept that comes to mind when considering this is heterochrony. This is a biological term, introduced to the art world by the French curator Nicolas Bourriaud around 2008. Heterochrony simply refers to the fact that different parts of an organism can develop on different timelines. One species might grow legs before a tail, another could grow its tail before its legs. At any moment, an organism might be advanced relative to its peers in one respect, and lagging behind in another. I think the experience of visiting a museum in a foreign country, such as the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, can be an occasion for the observation of heterochrony—a chance to experience an institution which has developed historically in a different way, an unfamiliar sequence, across its various attributes.

Lingnerplatz 1

01069 Dresden

* * *

Theo Honohan is an architectural historian and writer from Dublin, Ireland.