Sometimes a museum has the ability to transport us back into another era. This is the case with a new exhibition called ‘Peeping Tourist’ which opened in Durrës, Albania, last year. The exhibition offers an immersive experience, while at the same time telling the story of tourism in Albania during the Communist period. Albania was a Communist country from 1944 until the fall of the regime in 1991. During that period it was very isolated, closed off from the outside world (except for successive strategic alliances with Yugoslavia, Russia and China) by order of dictator Enver Hoxha.

You might wonder, therefore, about the role of tourism in a country that didn’t accept or want casual visitors – it used to be said that Albania was the only country in which you could get shot both trying to get in and trying to get out. ‘Peeping Tourist’ cleverly tells that story, through artefacts, documents, film footage, a recreated room, a bunker and even an optional ‘tasting’, providing an all-round experience for the visitor.

Founded by Brunilda Licaj and Arjana Isaku, both specialists in tourism and lecturers at the Aleksander Moisiu University of Durrës, the exhibition is a private enterprise. It is situated in a mid 1940s house belonging to retired teacher Albina Mima, in the historical centre of the city. A few years ago a small archaeological excavation took place in the courtyard of the house, which is located near to the Byzantine forum and Roman baths, and in the summer finds from the excavations in the Forum are still washed and laid out in the lovely small garden in between the citrus trees, flowers and vegetables.

On entering the house, which is clearly visible in the street due to a huge banner on the outer wall of the courtyard, the visitor finds themselves in a sitting room of an ordinary family home from the Communist period, with sofa, armchair and other seats and a small table on which sits a bowl of the famous red wrapped ‘Zana’ candies.

A local guide welcomes visitors to the exhibition and offers on the candies to visitors to the exhibition in the same way that they would have been offered to house guests years ago. The sweets (Zana means fairy in Albanian) were originally produced in the 1980s but are still in production today with the same wrapping. With this simple gesture, it feels like stepping back in time.

Taking a seat, visitors are shown the fixtures and fitting of the room. A television set is prominent, but we are reminded that there would have been only one channel available to tune into, and likewise with the radio. Foreign channels were forbidden.

Prized possessions are displayed on a wooden cabinet, including speckled glass fish ornaments produced in a nearby glass factory built by the Chinese in 1971. An empty can of Coca Cola on display illustrates how objects ‘from the West’ were sought after; the used can has now become iconic since featuring in and on the cover of Lea Ypi’s best-selling memoir ‘Free: Growing up at the end of History’.

Alongside family possessions, several cups and saucers, plates, and other ceramics bear the brand name ‘Albturist’. It is these objects which give us a clue to the main subject of the exhibition, the development of foreign tourism under the communist regime. Despite the closed nature of the country, a national tourism agency was established in the mid 1950s. The agency had different functions: it was partly for the promotion of Albania to countries of the former Eastern bloc (though tourists came from many other countries too), partly to bring some hard cash into the country, and also with the monitoring the actions and opinions of the foreigners, the latter motive bringing the fledgling industry under the wing of the Albanian intelligence.

The Albturist branded objects on display were made for the hotels in which the tourists stayed. These hotels were specially built to house tourists and large map showing their location is on display in the courtyard of the house. The itinerary of the tourists was tightly controlled: they travelled together, not independently, and were always accompanied by personnel from Albturist agency. The exhibition displays glossy leaflets produced by the state to showcase the hotels (several of which are still in existence today, though thankfully completely refurbished!). But being accompanied by Albturist personnel was not where the tourist surveillance ended: the hotels were bugged and monitored by the intelligence services. Hotel staff such as waiters were also encouraged to keep an eye on (and a distance from) the visitors.

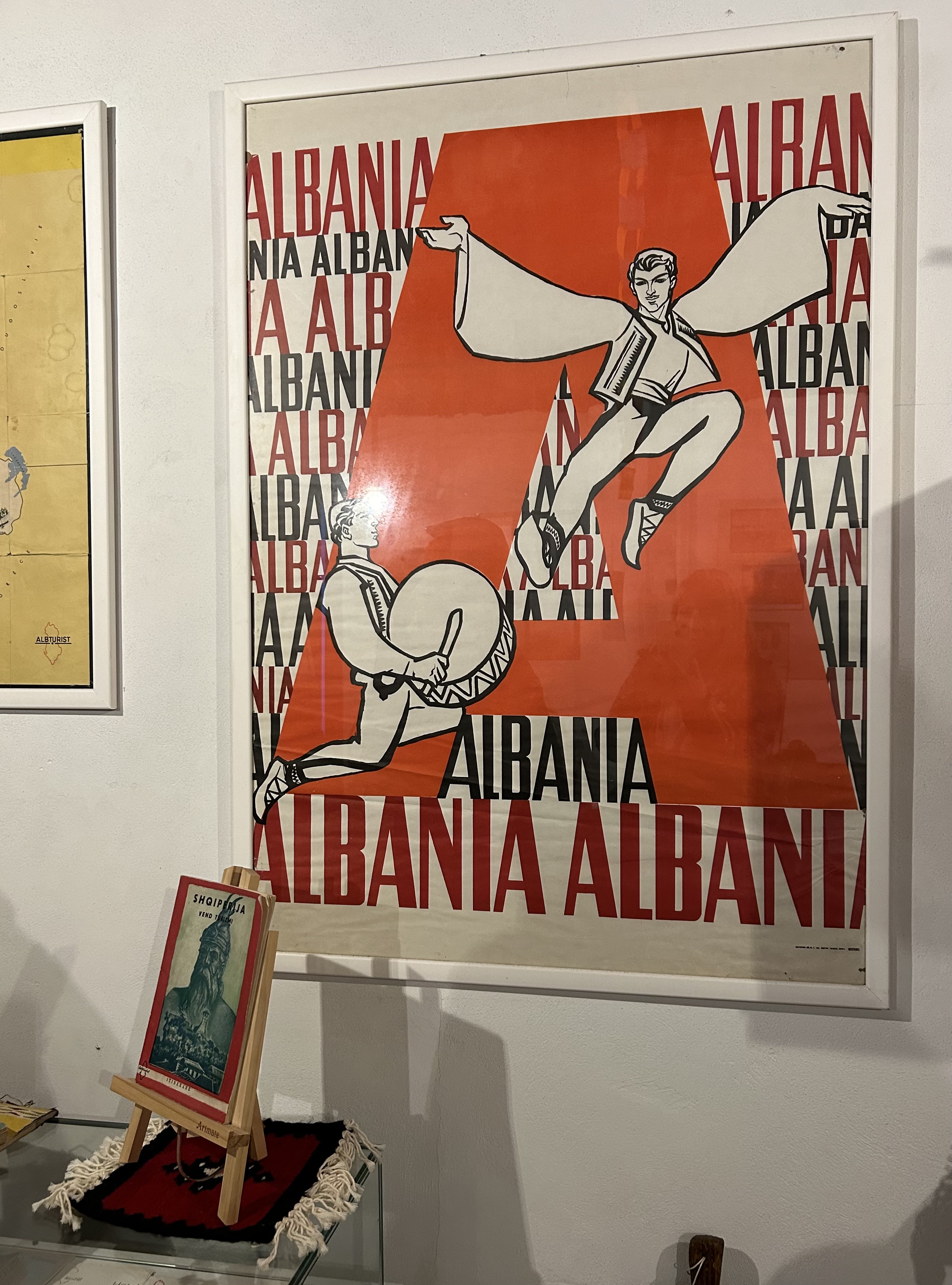

As well as leaflets and posters, guidebooks and phrasebooks were produced, examples of which are on display in Peeping Tourist. Everything was branded, even the coaches, which had Albturist emblazoned along the side and were specifically for the tour groups. It was a big investment for relatively few tourists, a sign that all was not as it appeared.

I found some of the most interesting material to be the copies of letters and documents from the Albanian State Archives, in which seemingly ordinary people from various countries expressed a wish to visit Albania, and asked permission to join a group. Visitors can also browse through files which detail the visiting tourists that became of interest and why. Co-founder Brunilda Licaj has been studying these documents for many years and estimates that, for example, of the visitors in 1984/5, 5 to 6% of them were under intensive surveillance by the Sigurimi (secret police), mainly via the hotels. At this point, it is clear that the name of the exhibition ‘Peeping Tourist’ is a clever one: though the authorities thought that many of the tourists were there to ‘peep’ or spy, it was actually the regime that was doing the ‘peeping’.

The collection of books on display includes some by foreigners who wrote up their experiences of travelling in Albania or who produced guide books themselves. Norwegian journalist Rune Ottosen’s book ‘Turist në Utopi’ shows a photo of him sitting on his bed in his Albanian hotel with short shorn hair. This is a big contrast to another photo in the book which shows how he looked when he arrived at the Albanian border with his 1970s hippy style hair down to his shoulders. Next to his book you can see barbers’ tools – at the border incoming tourists would be checked for inappropriate hairstyles and clothes and the barber and tailor would make the necessary adjustments.

The garden of the single storey dwelling houses an underground bunker built in the 1970s by the regime. It was built for use by several neighbouring families and could take up to 50 people, though I would certainly not want to spend much time in that dank, airless space with that number. Co-founder of Peeping Tourist Arjana Isaku recalls hearing the siren and having to take refuge in one of the underground bunkers, waiting for an enemy which never came. As a student she became an activist and took part in the protests leading up to the fall of the regime.

The bunker forms part of the exhibition, and visitors sit and watch one of the excellent films made specially for the museum. You can choose the length of film you wish to see (an average visit to the exhibition is 45 minutes to an hour). The films include fascinating archive footage and also some interviews. It was interesting to hear from former Albturist employees, but my favourite part was a recent interview with Rune Ottosen (who nowadays voluntarily has short hair) talking about his experiences.

At the end of the visit, you are invited to indulge in an optional extra, which might be a local raki (Albanian grappa) or Çaj Mali (mountain tea made from Iron Wort), Albanian coffee and ‘gliko’ a piece of fruit in syrup. I recommend this, as in addition to trying some really local fare, it is a small chance to experience typical Albanian hospitality, and to ask the knowledgeable exhibition guide any questions you might have.

Peeping Tourist is an excellent addition to the museums of Durrës: it tells a fascinating story, based on excellent scholarship, and has plans for expansion not only for the benefit of today’s foreign tourists, but also to educate young Albanians about their past. A whole new generation has grown up since the fall of the regime, and exhibitions like Peeping Tourist help people to understand the past, and for some, helps them come to terms with it. The excellent film shown in the bunker illustrates just how precarious life under the regime could be: we hear of an example of a musician at one of the hotels who lost his job after sitting on the lap of a Dutch tourist. After this transgression, he would find it very difficult to get another job, and this could have consequences for his whole family.

I recommend a visit to Peeping Tourist to get an insight into the history of Albania in this fascinating period, and if you can’t get to Durrës (or even if you can), perhaps you might like to read Free by Lea Ypi to get a ‘peep’ instead.

It is recommended to book via the website (https://www.peepingtourists.com/) to ensure a guided visit. The exhibition is currently open Monday to Saturday from 10am to 6pm (groups by arrangement) though subject to seasonal change, so it is best to check the opening times on google maps https://maps.app.goo.gl/wJG6c9qTWT1mmLU77. The entrance fee is 500 Albanian Lek for individuals but decreases for groups (again, details on the website). The ‘tasting’ is 100 lek. It is possible to just turn up during opening hours, but the guide may be busy with a group or booked in visitors, so it is better to book in advance.

Peeping Tourist is located on Rruga Mustafa Varoshi, in the centre of town. It is a 12-15 minute walk from the main Durrës bus terminus.

By Taxi:

Rruga Mustafa Varoshi runs parallel to Bulevardi Dyrrah, one of Durrës’ main streets, and starts on Rruga Fetah Bllaca behind the Aleksander Moisiu Theatre in the main square (Sheshi Liria). Taxi drivers may not be familiar with the exhibition as it only opened last year, so you may need to ask them for the theatre and then walk to the back of it. It is only a few metres along Rruga Mustafa Varoshi on the left.

On Foot:

If you are walking from the bus terminal, the easiest route is to take the Rruga Egnatia and then turn right when you reach Rruga Fetah Bllaca on the right. Rruga Mustafa Varoshi is a right turn on Rruga Fetah Bllaca.

* * *

Carolyn is a freelance lecturer with a ‘day job’ in philanthropy. Her background is in museums and education. She has worked at the British Museum and the Petrie Museum of Egyptology at UCL, as well as undertaking international museum consultancy. She has accompanied tours as a guest lecturer to such countries as Greece, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Syria and of course Albania, where she lives. Carolyn is on the Advisory Board of the World History Encyclopedia and Honorary Secretary of the Anglo-Albanian Association.