I had never expected to see any of the works of Ai Weiwei, let alone in Seattle. So I was thrilled to visit this exhibit when it came to Seattle.

His father, Ai Qing was a poet and member of the League of Left-Wing Writers in Shanghai and had been imprisoned by the Nationalists in 1935. In 1957, the year Ai Weiwei was born, Ai Qing was persecuted for ‘rightism’ and exiled with his family to a reeducation camp near the Gobi Desert in 1959. Ai Weiwei and his parents would remain there until 1975, near the end of the Cultural Revolution. It is no wonder that Ai Weiwei’s experience as a refugee in his own country shaped him into the political dissident and a spokesperson for the humanitarian crisis of global displacement. He studied in the U.S. for several years before returning to Beijing in 1996.

I thought this piece referenced the current Snake Year (in Chinese astrology), before I read the placard that described the 8.0 magnitude earthquake that shattered Sichuan province in 2008, killing over 80,000 people including thousands of students whose school buildings collapsed. Ai Weiwei recounts seeing nearby residences and hospitals still standing, and thought that the widespread corruption among contractors and government officials led to substandard materials and building practices that had caused the schools to collapse.

After the Chinese government failed to do so, Ai Weiwei assembled a volunteer organization to catalog the names and birth dates of 5,196 school students who lost their lives when their schools collapsed. Ai Weiwei says that in China, the snake is a symbol of unpredictable danger. His snake is made up of backpacks of the students who were found in the rubble.

My takeaway from this pieces was that corruption kills...

The Old Summer Palace in Beijing included Baroque-style palaces designed by the Jesuits serving the Qianlong Emperor (1735-95) during the Qing Dynasty. The centerpiece of the palace was a water-clock fountain devised by French astronomer Michel Benoist, comprised of twelve bronze waterspouts in the form of zodiac animal heads. Every 2 hours, one of the heads spouted water, and at noon, they all spouted at the same time. It was considered a technological marvel of timekeeping at the time.

At the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, the palace and grounds were looted by British and French troops and the heads were taken to Europe. Seven have been found and returned to Chinese museums since 2000, but since five of the original heads have never been found, Ai Weiwei redesigned the entire set, "blurring the line between original and copy, real and fake." I would discover that producing fakes of traditional Chinese artworks would be a recurring theme throughout this exhibit.

At first glance this appeared to be a stack of traditional porcelain vases glued together, until I stopped to study it and its stories of migration. The imagery combines traditional ceramic motifs such as dragons and flowers with images of repression including tanks, soldiers and refugee camps. The Eight Buddhist Symbols that would customarily ring the bases were replaced by what Ai Weiwei described as the Eight Needs of Refugees, including fire, a tent, good shoes, a life-buoy, and other necessities.

I cannot visit a museum without attracting the attentions of docents, as I again reached around the back of these furniture pieces, and nearly layed on the floor to get some of these shots. I was fascinated with his tables and the joinery techniques which made the undersides as beautiful as their tops. Although these pieces were deemed sculptural rather than functional, I would find a place in my home for any of them, especially those whose legs are attached to the wall.

The original tables date to the Ming and Qing dynasties. Ai Weiwei hired artisans to tear them apart and reassemble them in new forms, using traditional joinery techniques. No nails were used in this process, and the artisans took great care to preserve the original patina. Other pieces in this exhibit were made from construction debris which Ai Weiwei used to meditate on cultural systems of value. Wood pillars, doors and windows salvaged from demolished buildings take on new forms, and challenge our idea of what is useful vs useless; trash vs. treasure; genuine vs. counterfeit. His work ultimately undermines the extreme positions of binary thinking.

As usual, I didn't capture some of the pieces that I should have. There was a wall of jars filled with dust from the ancient pottery that Ai Weiwei intentionally destroyed, adjacent to a line of individual bricks in customized boxes, that (I think) was an homage to the bricks his father was forced to make in the internment camp where his family lived. Ai Weiwei seemed to have high regard for architectural pieces but very little regard for antique porcelains.

There were paintings by other artists that Ai Weiwei reproduced in Lego. I paused to admire his Lego cover page of Mueller's Report which covered an entire wall. Here is an 'easy chair' carved from a block of marble. There were two piles of sunflower seeds – each shell individually crafted from porcelain by 1600 artists in Jingdezhen, a city renowned for its porcelains since the Ming dynasty. A case displayed Ming dynasty vase that Ai Weiwei painted with the Coca Cola logo, one of the first American corporations to sell their product in China. The bicycle sculpture of "Flying Pigeons" was in a room of its own, with a pile of parts along one wall that stretched the entire length of the room. It was an homage to when bicycles were the main form of transportation in China.

The last photo is one of the first you will encounter when you visit (pictured at top of page), showing Ai Weiwei intentionally destroying a Han Dynasty vessel, both as performance art and (I think) a premise of testing the shutter speed of his friend's new camera. It became iconic for drawing attention to the intentional destruction caused by present day urbanization projects, and the wrecking of historical sites, art and books during China’s Cultural Revolution.

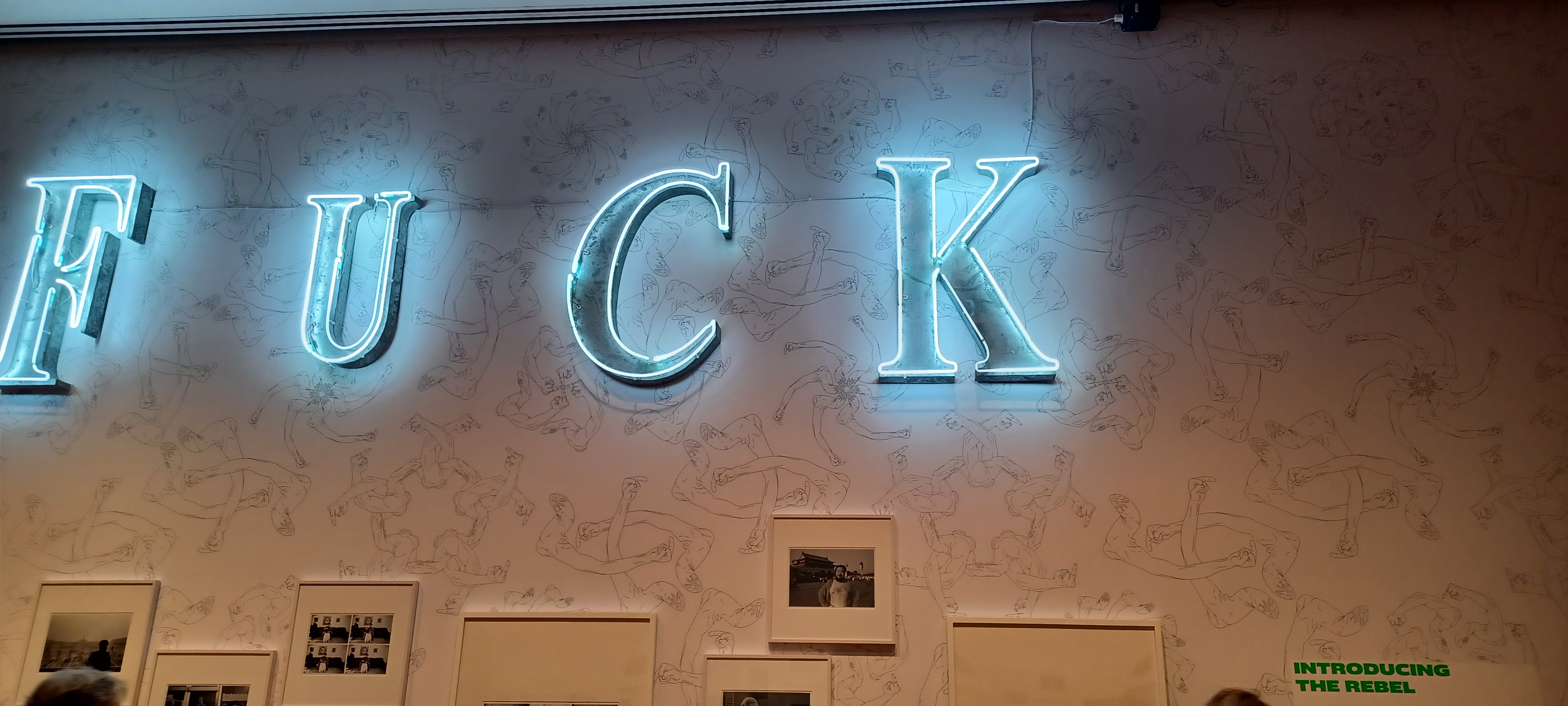

It was one of a series of photographs - some fairly irreverent - displayed under a large neon expletive which in Mandarin is pronounced "fah-kuh'. The neon letters headlined an exhibit entitled “Uncooperative Attitude” that Ai Weiwei ran for about five minutes in 2000 before it was shut down by authorities in Shanghai for being obscene.

This exhibit runs through September 7, 2025 at the Seattle Art Museum. I highly recommend it as it offers plenty of introspection and inspiration in this current age of rebellion.

https://seattleartmuseum.org/whats-on/exhibitions/ai-weiwei

Additional photos are posted to Daveno Travels

* * *

Heather Daveno hails from Seattle, Washington. She is newly retired and divides her days in between three 501c3 organizations, where she is currently writing grants, managing social media, running a makerspace and making hats and clothing for a living history museum called Camlann Medieval Village. She is also writing a family history (The Matriarch Diaries) as well as a retrospective of her gig as a hatmaker (The Storied Hat). You can see her current textile projects at August Phoenix Mercantile and her travels at Daveno Travels.