A few weeks ago, I was home working on a story and watching the local news. I saw a segment on a new exhibit at the New York State Military Museum and Veterans’ Research Center here in Saratoga. I was fascinated. I’d never heard about the man they were referring to or his backstory before.

I visit this museum frequently, as it tells many fabulous and moving stories about New York’s military history and the service and sacrifice of our veterans. Many of the exhibits change often, while others are permanent. I’ve been fortunate enough to meet several of the veterans featured at the military museum and have written numerous articles about them and the museum itself.

Some of the displays showcase the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, naval history, World War I, and World War II, to name a few. Much thought goes into each historical exhibit, and I usually spend a few hours each time exploring and learning more about the contributions of New York’s military men and women in defending our country.

The story of Richard Marowitz is one I’m glad I heard about during the Channel 13 News segment, and I’m grateful I was able to see it in person the very next day. It's wonderful that his children – Linda, Larry, and Roberta - entrusted the museum with artifacts related to their father’s service during World War II. This keeps world history alive, and future generations will benefit.

I wondered why the group of young soldiers was called the “Rainbow Division.” I was pleased to learn that during the unit’s formation in 1917, then-Colonel MacArthur claimed it “stretches like a rainbow from one end of America to the other.” The unit, which included thousands of New Yorkers, was reactivated in 1943 for service in Europe during World War II. When they landed in France in December 1944, they were immediately drawn into combat during the Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945, the unit crossed the Harz Mountains, breaking through the Siegfried Line.

In late April, they sped their jeeps through German convoys and enemy positions, firing their weapons the entire time. The closer they got to Dachau, the worse the stench became. When they reached the camp, among the first American soldiers to enter that hellhole, the GIs discovered a horror that belied words, viewing over 5,000 dead bodies stacked inside rail cars and on the grounds of the camp, and discovering over 30,000 emaciated prisoners – some of whom fell dead where they were standing moments before. They experienced this firsthand. The Dachau Concentration Camp, the first one established by the Nazi, was one of their greatest atrocities. Here, Hitler’s henchmen brutally murdered tens of thousands of prisoners – including Jewish men, women, and children. Their sole crime was in being Jewish, holding tight to their religious faith.

Immediately after Dachau was liberated on April 29, 1945, by the 42nd Rainbow Division, alongside two other divisions, scouts from the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, to which Private 1st Class Richard Marowitz belonged, were ordered to travel to nearby Munich to search German Dictator Adolf Hitler’s apartment. The scouts arrived in Munich on April 30. The front door was opened by Hitler’s English-speaking housekeeper, who referred to them as ‘ruffians’. She asked why everyone was in such a tizzy – Hitler was a good man. The soldiers rushed past the woman, scouring every inch of the apartment. Although there remained art on the walls and furniture in the rooms of this dwelling, Hitler’s personal belongings appeared to be missing.

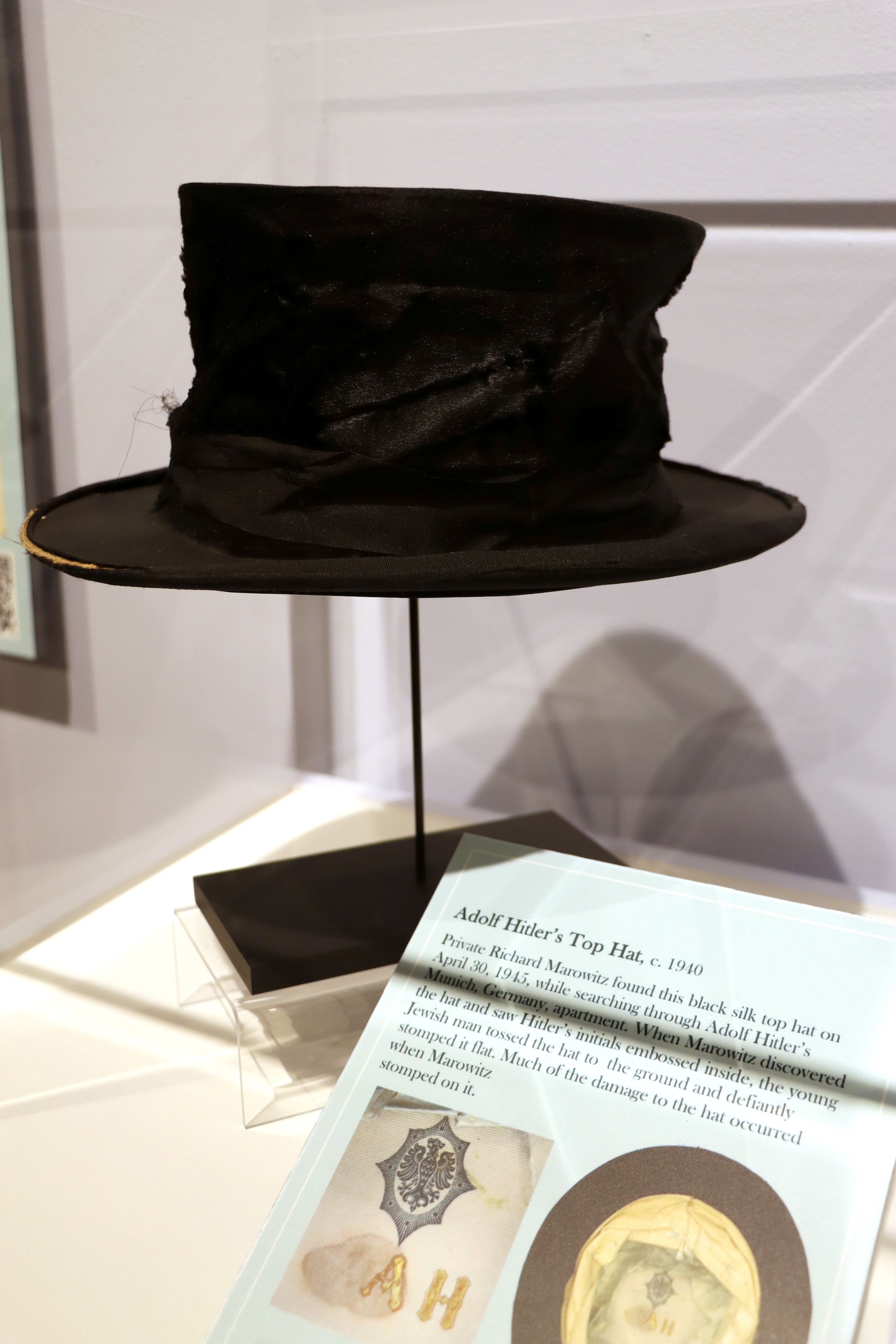

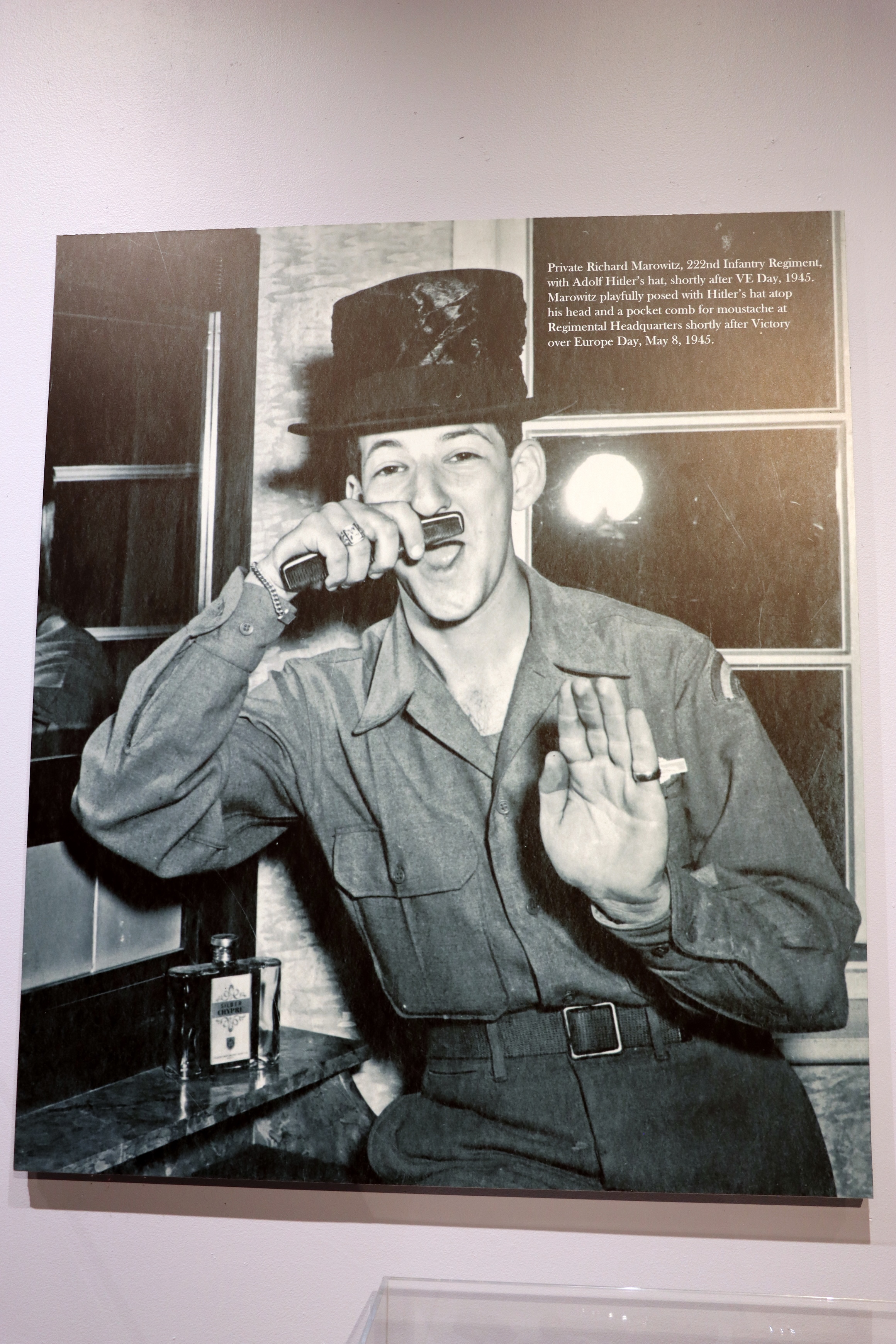

When 19-year-old Marowitz entered a bedroom, which turned out to be Hitler’s, he opened empty dresser drawers. A closet was also empty, except for one item. Richard saw something dark on the top shelf. As he climbed onto a chair to examine it, he discovered a gorgeous black silk, formal top hat – one that Hitler was often photographed or filmed wearing during his dictatorship. He pulled it down, turned it over, and inside found the initials A H in large gold lettering. “I put two and two together and swear I could see his face and head in it!” Richard told many people over the years. “To this day, I still can!”

Later, in a short 45-minute documentary I watched to learn more about this event, the soldier explained that the atrocities they’d seen the day before inside the camp angered and sickened them. They were profoundly affected. “I was so angry, I threw the hat down, and jumped from the chair, stomping on it.” And he didn’t stomp on it once or twice; he kept stomping on it, flattening it out, expressing a tiny bit of the emotions he and the other soldiers were feeling in the moment.

When asked in an interview if he was fearful entering Hitler’s apartment, Richard laughed. “No, not really. It was more fearful going back out into the town – we were the only Americans there at the time. There were 12 of us., Munich wasn’t taken over until sometime that afternoon.” The GIs had been warned that the main German forces had left the area, but there were SS snipers around, so they should be super-vigilant, exercising extreme caution.

The GIs later learned Hitler had committed suicide that same day, Marowitz joked that it was “because some skinny Jewish kid from Brooklyn stomped all over his favorite hat!”

Hitler’s Hat came home to the States, where it was placed in a duffle bag and tucked away in the cellar of Mr. Marowitz’s home until the mid-90s. He was a member of the Jewish War Veterans. He attended a meeting where soldiers and their families were asked if they had any souvenirs from the war. That’s when the hat came out of hiding, so to speak. Richard began accepting speaking engagements at schools in and around Albany, New York, sharing the things he and his comrades had witnessed and lived through during the Holocaust years and the murder of more than 6 million Jews. Richard hoped that by speaking about the war and the horrors he’d seen, he'd help prevent anything like it from happening again.

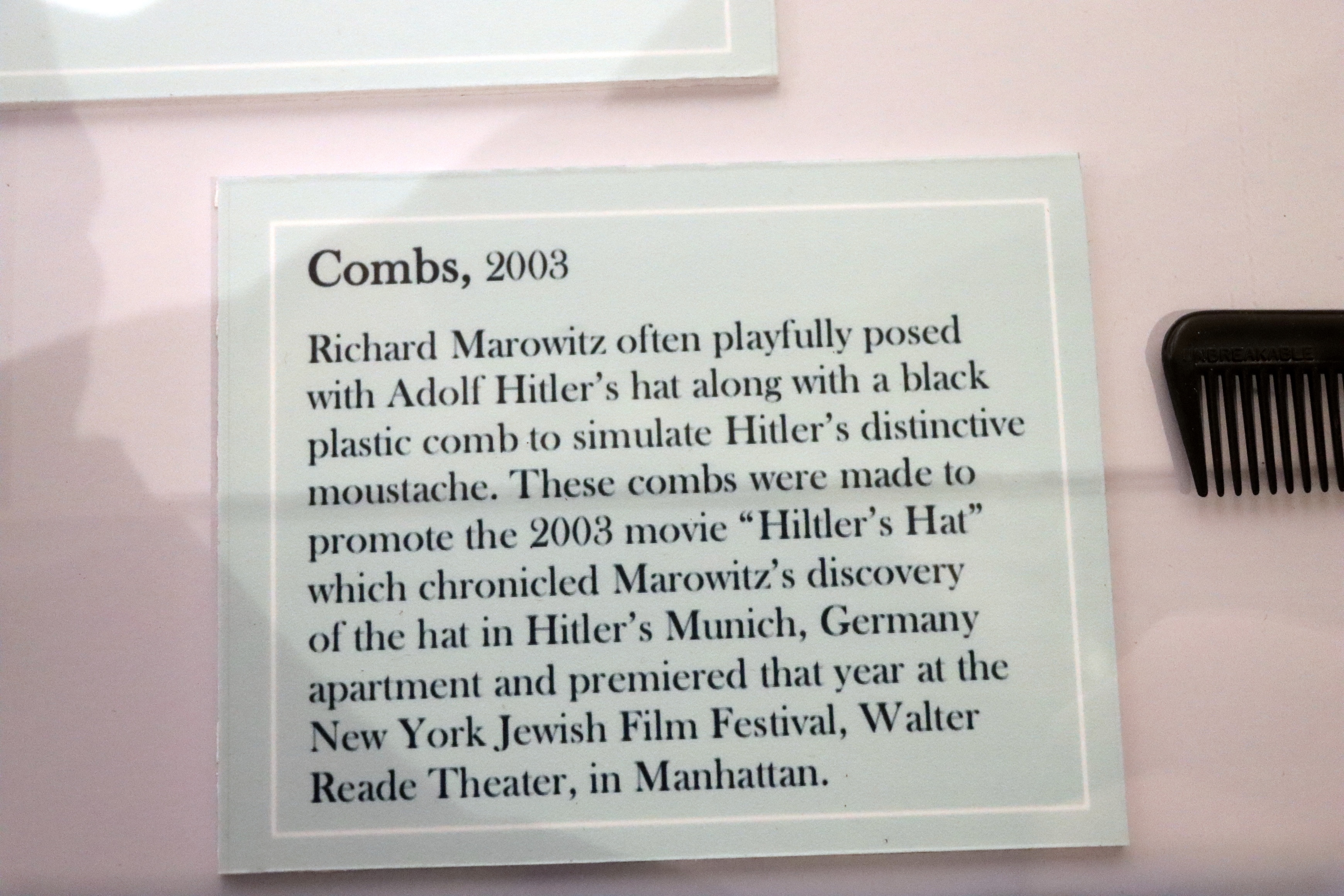

Word got out about the top hat, and the fascinating true story was picked up by documentary filmmaker Jeff Krulik, who featured the veterans of the 42nd Rainbow Division in his 2003 film, “Hitler’s Hat.”

I had mixed feelings standing in front of the exhibit. It was surreal, seeing something that had once belonged to such a horrific time and such a hateful dictator. I was emotional, thinking about all of the murdered humanity, and about the veterans who fought to save and liberate them. They didn’t know what horrors they’d find when entering the camps constructed by the Nazis. I cannot imagine what it was like to attest to the extent Nazis would take, the lengths they would go to obliterate entire races, because they were different.

History is vitally important, as it gives all of us insight into the past, vowing that things like this must never, ever happen again. Thanks to soldiers like Richard, history remains alive, front and center at this museum and others like it. Thank you, thank you.

Below are two YouTube links that speak about Hitler’s Hat and the man who ‘liberated’ it from the apartment in Munich.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7KH_GE-Cv78

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rAH9Gmx5D-4&list=PL56Af0hUHKz81m6oOtB7Tg4n8Rw6QTqME&index=3

If you visit:

Address: New York State Military Museum and Veterans’ Research Center

61 Lake Avenue, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866

(518)-581-5100

Hours of Operation: Closed from Monday, May 12, 2025, to Monday, June 9, 2025, for HVAC renovations.

Usual Hours: Tuesday – Saturday 10:00 am-4:00 pm Closed Sunday and Monday

Parking: On-street parking

* * *

Theresa St. John is a freelance travel writer, photographer, and videographer based in Saratoga Springs, New York. She is interested in WWII history, museums, food, slavery, the Underground Railroad, interviewing interesting people, restaurant reviews, local travel, anything ghost-related, and the Erie Canal, among other things. Theresa loves to travel and sinks her feet into the moments of places she visits. Her photography essays, along with the written word, help tell the story to readers everywhere.