When I say ‘Salford’, what comes to mind? For me, I see a picture of urban landscapes, sprawling with churches, shops and rows of red brick terraced houses. I see all kinds of people; tall, short, old and young going about their daily business, gloomy grey skies and billowing dark plumes of smoke erupting from the chimneys of factories. One thing remains constant through all these images, I see them in vivid oil paint. Of course, these images are that of renowned Salfordian artist L. S. Lowry (1887-1976).

Lowry has always been one of my favourite artists. I think it’s probably something to do with one of my art classes when I was in primary school. I remember the day clearly, we spent the morning watching a film about Lowry and then in the afternoon we had a go at producing our own versions of Lowry’s paintings using oil pastels. Of course, as a nine year old, what I produced was a far cry from Lowry’s famous pictures but what I learned about him stayed with me that day.

Although not from Manchester or Salford originally, I’ve called this part of the world my home for the past seven or eight years. It’s a place that’s renowned for all manner of things including the long-running TV soap opera Coronation Street, The Hacienda nightclub, the birthplace of the Suffragette movement, Canal Street and the Gay village as well as the Manchester United and Manchester City football clubs. But it’s also home to many museums and galleries, including The Lowry located in Salford Quays. It’s one of my favourites and in this article, I’d like to share with you some of its wonders.

The Lowry (pictured above, photo: Nathan J Hilton) is surrounded by a rich history and an energetic present. The building is located within Salford Quays, which has been one of the United Kingdom’s largest urban regeneration projects. The area was formerly home to the Manchester Docks, part of the Manchester Ship Canal network which was opened in 1894 turning a landlocked city into one of the country’s largest and busiest ports. After the docks closed, the 1980s and 1990s saw major work done to change what was a declining port into an urban centre for retail, residential housing, entertainment and culture. Other major landmarks include the Imperial War Museum North, Manchester United’s Old Trafford Football Ground and MediaCityUK; the area home to media organisations such as the BBC and ITV Grenada Studios.

The Lowry itself is much more than just a gallery, it’s also a visual arts and performance centre. Within this complex, you’ll find The Lyric Theatre, the largest stage outside of London which can hold up to 1,730 people. You’ll also find the Quays Theatre which can seat audiences up to 440, as well as the Studio Auditorium which seats a more modest 150. Here performances such as ‘The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe’ and ‘Les Misérables’ are shown. Under this very same roof sit The Lowry Galleries, where The Lowry Collection is on permanent display.

It was on a fittingly gloomy and overcast Tuesday morning that I decided to visit The Lowry. After a quick bag search by security, I was directed up the escalator to The Lowry Galleries, where before entering a Visitor Assistant warmly welcomed me, explained the layout of the galleries and highlighted the contactless card donation device for if I wished to make a donation. Many of our museums and galleries in the UK rely on donations so as I’m in the fortunate position of being in full-time work, I always try to give a £5 donation for my visit.

The first part of the gallery currently constitutes The Lowry’s ‘Days like These’ special exhibition. It’s an exhibition made up of paintings, photographs and poems submitted by local Salford residents, with the aim of highlighting their experiences of living in lockdown in 2020 brought about due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This isn’t a doom and gloom exhibition, on the contrary, it was colourful and vibrant while also being inspiring and uplifting. One particular highlight was the short film entitled ‘A Calmer Place’, filmed and edited by David Warren. It featured the highs and lows of one man’s experience of living in lockdown. He recalls how the feeling of being a prisoner within his own home, the lack of socialisation and the relentless barrage of Zoom calls all began to take a serious toll on his mental health. The film then shows how the man goes out into nature by himself and goes open water swimming in a freshwater lake. This is his ‘calmer place’, a place where he can, if only temporary, forget all of his worries and feel truly present and alive.

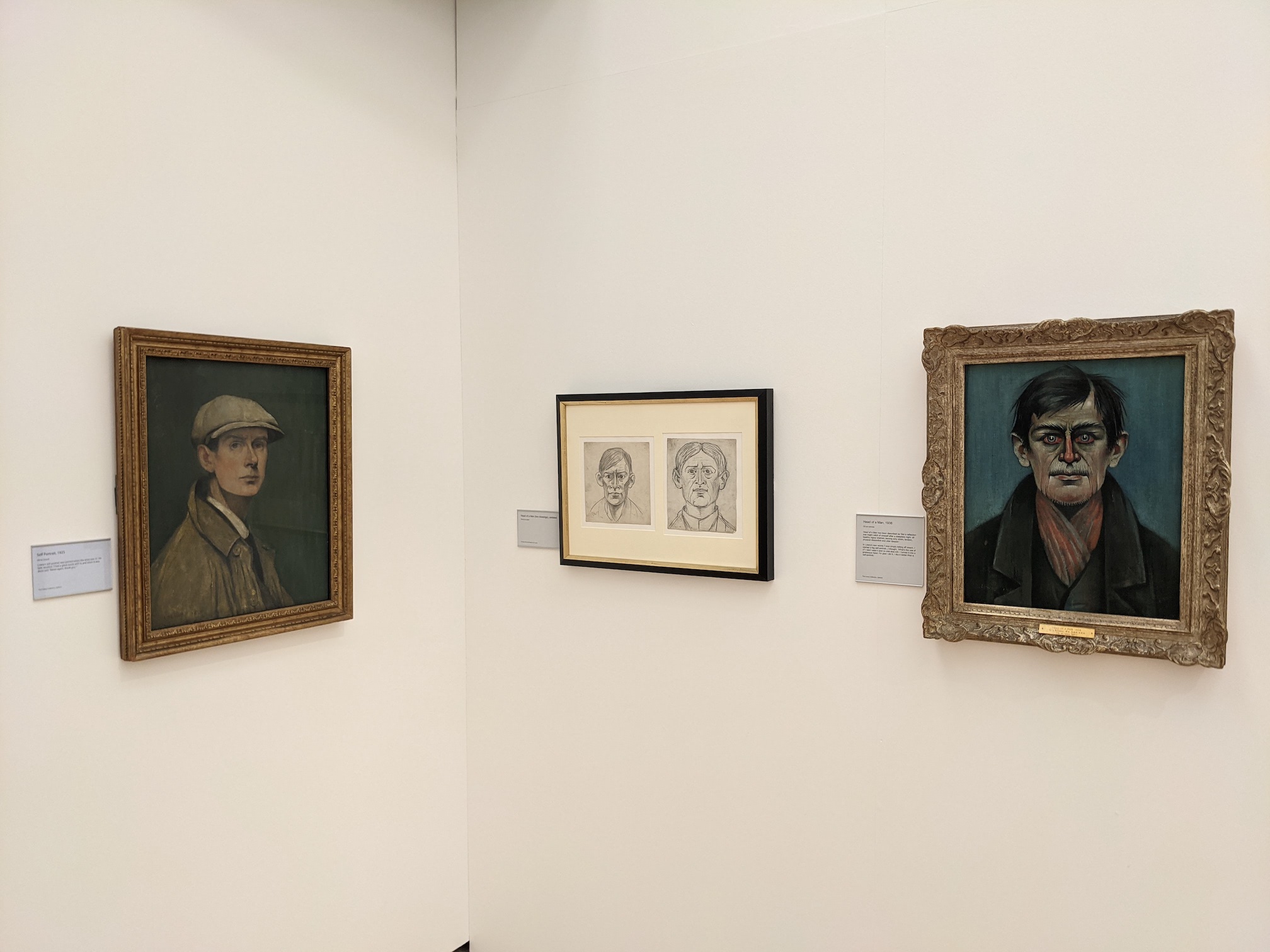

Carrying on through the space, I reached the part of the gallery where The Lowry Collection is displayed. Upon entering the gallery I couldn’t help but notice the juxtaposition between two of Lowry’s most famous self-portraits; ‘Self Portrait’ (1925) and ‘Head of a Man’ (1938). The former showing a smart and respectable young man, painted in a warm lovely detail but the latter portraying an almost grotesque and terrifying figure, staring directly at me, as if looking at something deep within me. Both are self-portraits of Lowry but painted at different times in his life. It makes you wonder, are we always one person, or are we constantly shifting and morphing, in the process becoming different people?

The next painting that catches my eye is one of my favourites and is typical of those images that come to my mind when I think of Salford; entitled simply, ‘Industrial Landscape’ (1953). The painting includes everything that I think of when I think of Lowry’s work; the row of red brick terraced houses, the crooked so-called ‘matchstick men’ figures of people likely on their way to work or school, the iconic factories that litter the landscape and their respective chimneys which can be seen pumping black smoke into the grey monotonous sky above. If I could have any Lowry painting hanging on my wall, this would be it.

Almost all of the pieces are hung on the walls of the gallery, except one that sticks out like a sore thumb in the centre of the space; in a perspex box positioned on a wooden plinth sits a selection of Lowry’s materials. It includes some of his paintbrushes, his iconic trilby hat and a small piece of board that he used for mixing coloured paints. I couldn’t help but wonder if any of the paintings that adorned the walls around me were painted using paints mixed on this board.

As I turn the corner, I’m drawn towards another painting, this time it’s ‘The Cripples’ (1949). Far from acceptable modern-day language but typical of its time, ‘The Cripples’ is a not so flattering depiction of many of the disabled people who lived around Manchester and Salford at the time. This is one of the few paintings that confuses me, I don’t quite know how to feel about it. On the one hand, it can be seen as a comendable effort to highlight those people who had been neglected and disabled by a society that didn’t really care for them but on the other it could be seen as a bit of a cruel joke; distorting these people’s bodies and contorting their faces in the process. Ultimately, it makes me feel something, and after all, isn’t that what art is supposed to do?

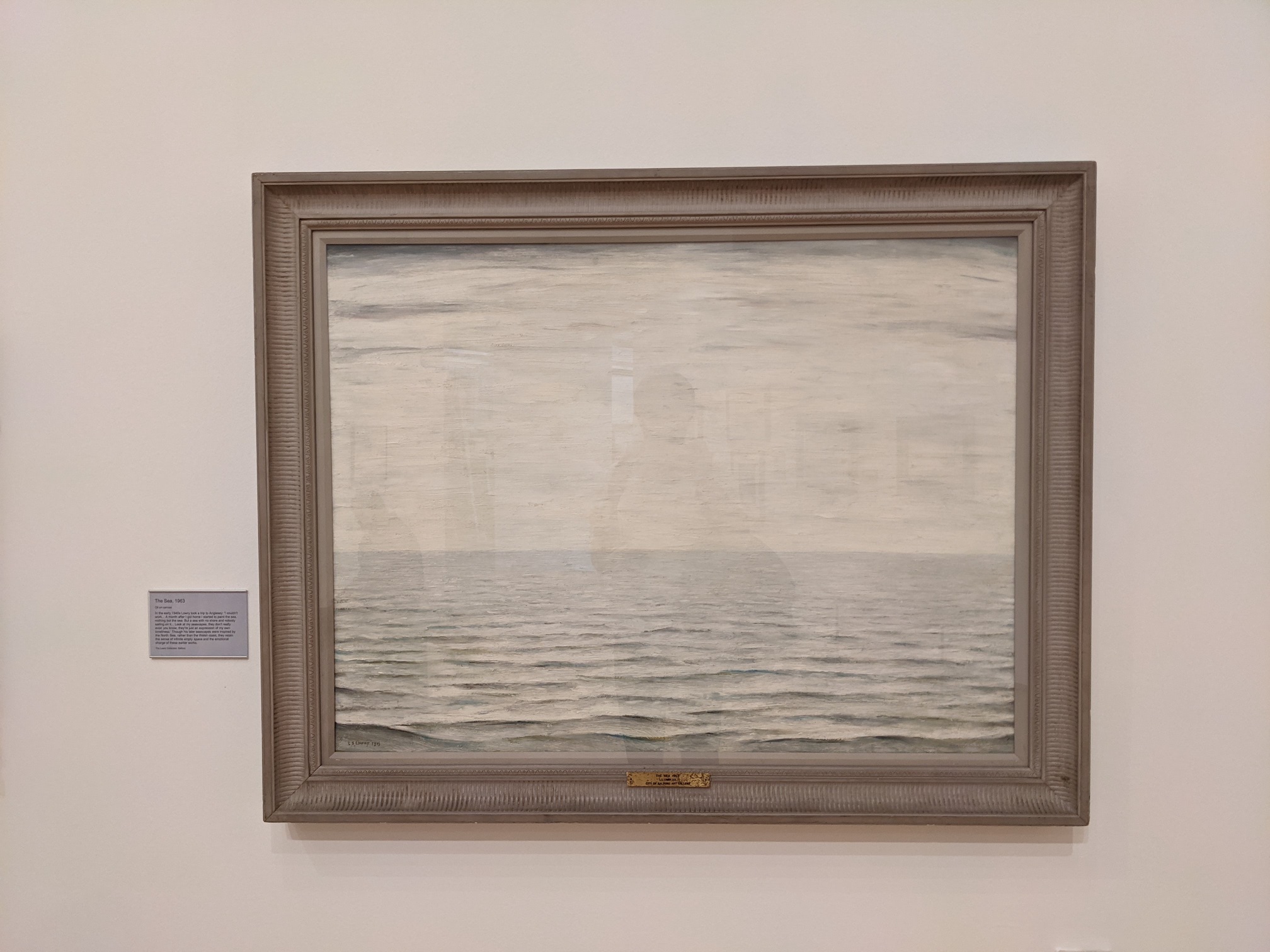

In one of the last sections of the gallery is a small room that displays some of Lowry’s more rural landscapes as well as some of his seascapes that he created towards the end of his life. I really enjoy in particular ‘The Sea’ (1963). Even though the bottom half of the painting is very different to that of ‘Industrial Landscape’ (1953), the top halves of both pictures are almost the same. Lowry potentially didn’t mean anything by this, perhaps this is just the way he painted clouds but to me, it connects two very different paintings of very different places. There’s something quite emotional about this painting as well. It’s well documented that Lowry led quite a lonely life, spending much of his time caring for his mother when he wasn’t painting in his attic room or collecting owed monies as a rent collector. When she died, it broke him. He never married nor did he ever really have a romantic relationship of any kind. It’s possible then that these desolate and barren seascapes were a reflection of his own state of mind. I think we can all relate to feeling a similar way at some point in our lives.

There’s one final small room within the gallery and it features a television screen and a few rows of chairs. Here, a twenty-minute film plays about Lowry, a sort of mini-documentary giving an overview of key parts of his life and his most notable works. It really helped contextualise many of the pieces of art that I had just been looking at. For me, the most interesting part of the film was towards the end, where a reporter for The Guardian recounts his experience photographing Lowry’s home shortly after he had died. There were that many paintings scattered around the house it was hard to make out the walls of the building! Seeing the spaces not just where he made his art, but where he ate, read, slept felt personal and felt as if after this whole visit to The Lowry I had really got to know him as a person.

If you ever find yourself in Manchester or Salford, I implore you to pay a visit to The Lowry. L. S. Lowry’s work isn’t just an important part of modern British art history, it has a strong social value to it. Through his work, he allows us to understand the rich social history of the North West generally; more specifically, Manchester and Salford, and how the industrial revolution changed this part of the world, its landscape and people. Lowry’s work, to me at least, is more than just appealing art, it’s an opportunity to explore part of my own identity, what it means to be British and as an adopted Mancunian.

The Lowry Galleries are free to visit but donations are encouraged. They’re currently open Tuesdays to Fridays 11am-5pm and Saturdays to Sundays 10am to 5pm.

* * *

Hi there! My name’s Callum and I’m a museum professional based in Manchester. I live and breathe museums. If I’m not working in a museum, I’m visiting one - I really should get some new hobbies! The one thing I love about museums is that they’re places for lifelong learning. Whether we’re aware of it or not, everytime we go to a museum we’re learning in some way. It doesn’t matter where you are in your life, museums offer this opportunity to learn and I think that’s really special. I run a blog called Learning in Museums where I explore this in more detail. Feel free to have a read of some of the articles and let me know what you think or just say hello if you fancy a chat. You can contact me via Twitter @CallumW122 or via email at callum@learninginmuseums.co.uk